Text by Maxim Popenker, © 2014

The term “Assault Rifle”, despite its widespread use, is still controversial, because general agreement is not yet there on exactly what it means.

The concept of an assault rifle first became well known towards the end of WW2 and shortly after, as a political/propaganda measure on the part of Adolf Hitler, although both the basic concept and the term itself do have a noticeably longer history.

The earliest use of a similar term, known to this author, dates back to the 1918-1920 timeframe, when noted US small arms designer Isaac Lewis produced a series of experimental automatic rifles which he called “Assault Phase Rifles”. These rifles fired standard US Army issue rifle ammunition of the period, the .30 M1906 (.30-06, 7.62x63mm), and were in direct competition with John Browning’s M1918 BAR Automatic Rifle. Both Lewis and Browning automatic rifles were designed along the same conceptual lines of “Walking fire”, originated by the French in around 1915 and first implemented with the ill-fated CSRG M1915 “Chauchat” Machine Rifle. This concept called for a man-portable automatic weapon whose primary function was to provide suppressive supporting fire for infantry during assaults on entrenched enemy positions. In fact, this concept called for THE “Assault” Rifle, but its early implementations, such as CSRG M1915 and BAR M1918 mentioned before, or the Russian Fedorov M1916, had some inherent flaws.

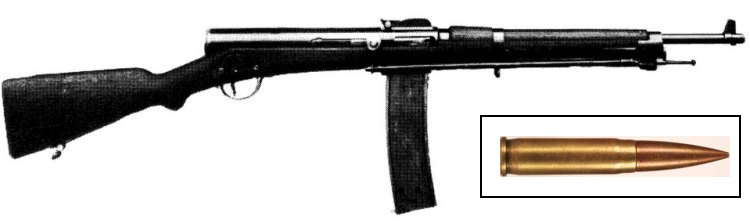

Experimental “Assault Phase Rifle” by Isaac Lewis, developed circa 1918 to compete with BAR M1918. It fired the same powerful .30 M1906 (.30-06) rifle ammunition

The major source of problems with these “first generation assault rifles” was their use of rifle-sized ammunition. Designed during the late 19th and early 20th century, this ammunition was quite powerful, capable of being fired the distances necessary for long range suppressive volley fire. This arrangement was the standard and widespread infantry practice, until the mass adoption of machine guns during WW1.

This “extra power” from the ammunition type resulted in significant recoil, as well as a noticeable carrying weight of the ammunition and of the guns that fired it. This resulted in an increase in manufacturing costs, in logistics costs and also making such automatic rifles difficult to manage in combat.

The most logical solution to this problem was to reduce the power of the rifle ammunition to a more manageable level, but still with the power necessary for most (but not all) typical combat scenarios. Traditional rifle cartridges of the era had a ‘lethal range’ well in excess of two kilometers. However, under combat conditions no one (well, almost no one, but more on this later) can expect an average soldier to be able to hit a man-sized target at ranges longer than 300-500 meters. Furthermore, decreasing the power of rifle ammunition has several benefits. These include: savings on raw materials, powder, logistical cost per round, increased combat load (as in number of rounds carried per soldier), decreased weight, size and cost of rifles, decreased recoil, which is in turn conducive to better accuracy.

This concept was supported by practical experience gained during the Great War with the French-issued, US-made Winchester M1907 self-loading rifles. These handy carbines were initially brought from the USA by the French Army to arm aircraft observers. Machine guns soon replaced rifles in this role.

On the other hand, compact and handy carbines that fired a good “stopper” cartridge (.351 WSL, also known as 9x35SR, with round-nosed bullets) were excellent weapons for close combat on the battlefield. Fitted with extended magazines (15- or 20-round capacity), bayonet mount, and, in some cases, converted to fire in full-auto, these little rifles became progenitors of the modern “Assault Rifle” concept.

Fundamentally, an ‘Assault Rifle’ is an automatic carbine firing reduced-power ammunition. This reduced-power ammunition is also known as intermediate power ammunition (or simply “intermediate cartridges”). It is less powerful than standard military rifle ammo yet more powerful than typical handgun ammo.

Winchester M1907 Carbine in “Assault” configuration (as used in WW1 by the French army) and its .351WSL “intermediate power” round

The first intermediate cartridges..

As early as 1918, several countries began to work with this “reduced power” concept, including France and the USA. The French attempt was the Ribeyrolles M1918 automatic carbine which fired specially designed 8x35SR ammo, based on the .351WSL cartridge but modified to accept standard 8mm Lebel pointed military bullets. The American attempt, known as the Winchester-Burton machine rifle, also used a cartridge based on the .351WSL. This purpose-designed round was called .345WMR (Winchester Machine Rifle), and used a pointed bullet of approximately 9mm caliber.

During the early 1920’s, Switzerland and Italy joined the club of ‘intermediate power’ developers. They produced their own cartridges and automatic or semi-automatic weapons to fire them. By the mid-1930’s several other countries (e.g. Denmark and Germany) attempted to develop their own versions of intermediate power cartridges and the automatic weapons to fire them, but none were adopted at that time.

Ribeyrolles M1918 Automatic Carbine with its 8x35SR cartridge |

Winchester-Burton Machine Rifle with .345WMR cartridge. This unusual weapon has two top-mounted magazines in V-shaped configuration. |

Here’s the million dollar question: if the concept was known and found worth researching as early as 1918, why wasn’t it fielded until 1942? There’s no simple answer, but we can speculate on some of the reasons:

1) The military, especially the higher ranks, are historically quite conservative. The very concept of arming every infantryman with a rifle capable of firing a full combat load of 100 rounds in about a minute was quite alien to many commanders. The amounts of ammunition needed were astounding to those who grew up during the era of bolt action rifles with magazine cut-offs.

2) Despite the weight and cost savings per round offered by intermediate cartridges compared with standard rifle rounds, automatic weapons greatly increased the expenditure of smaller rounds. This would still put additional strain on manufacturing and logistical capabilities, not to mention budgets, which were drastically cut back after the end of WW1.

3) After WW1 machine guns were considered to be essential infantry arms, and using reduced power ammunition in machine guns was out of the question at the time. Therefore, this would require keeping two different rounds in the supply chain, making logistics even more complicated.

4) Up until the mid to late 1930’s, typical targets for infantry rifle fire included other battlefield objects besides just enemy personnel, such as horses (cavalry was still considered important by many nations), armored cars and low-flying combat aircraft. All of those targets are tougher than an average human being, and using reduced power ammunition against these types of targets would place troops at an obvious disadvantage.

Overall, it appears that most militaries of the interwar period considered the “full power” semi-automatic rifle as the next logical step in the evolution of individual infantry arms. Some nations tried to create automatic rifles (such as the Soviets with their unsuccessful AVS-36 rifle), but the majority were set on the self-loading only types. One notable attempt to reduce the power of the standard infantry rifle was made by the Americans during the late 1920’s – early 1930’s, when they tried to replace the old and powerful .30-06 (7.62×63) cartridge with a .276 (7×51) cartridge, developed specifically for the new semi-automatic military rifles. This attempt was cancelled, though, mostly on financial and logistical grounds.

Despite all of these reasons not to adopt reduced power automatic rifles, military experts and industry engineers kept working on the new concept. Among these were the Germans, who took the intermediate cartridge route in 1935. By 1940 the Department of Armaments, German Army (Heereswaffenamt, or HWaA in short), had settled on the 7.92×33 intermediate power rifle cartridge, developed by the Polte company. From a performance point of view, the nominal caliber of 7.9mm was inferior to the originally proposed 7mm caliber, but 7.9mm was chosen for its manufacturing benefits. New barrels, cases and bullets could be made on existing machinery, originally used to produce barrels and ammunition for the standard infantry 7.92×57 Mauser cartridge.

The 7.92×33 round, also known as the 7.92 Kurz (short), fired an 8 gram bullet at about 690 m/s; with a muzzle energy of about 1900 Joules. Compared to the 7.92x57mm (8mm Mauser) with a standard sS bullet (12.8 gram at 800 m/s, 4100+ Joules), this new “Kurz” cartridge generated about 50% less recoil and also weighed about 40% less (16.7 g as compared to 26.9 g).

Once this promising new round was selected, contracts were issued to the Haenel and Walther companies to develop a new class of automatic weapons – the so called “Machine Carbines”, or Machinenkarbiner in German (MKb for short). By 1942, two versions of the German MKb.42 machine carbines (MKb.42(H) by Haenel and MKb.42(W) by Walther) were tested at the Western front, and the concept was found to have its merits. However, official adoption was delayed by troops requesting some changes (including conversion to fire from a closed bolt as opposed to the original “submachine gun style” open bolt) and more importantly, by personal orders from Adolf Hitler to cease all development of new classes of small arms.

In order to circumvent Hitler’s orders, the next version of the Machinenkarabiner was renamed to Maschinenpistole (submachine gun, a class of weapons already in widespread service with the German Army), and entered production in 1943 as the MP-43. Once reports of the MP-43’s success at the front reached German Headquarters in 1944, Hitler finally approved mass production of the new weapon and its associated 7.92mm Kurz cartridge, personally christening it “Das Sturmgewehr 44” (Stg.44 in short), which means “Storm” or “Assault” rifle. It was pure propaganda, as at the time Hitlers’ Germany was all about defense instead of the earlier “Sturm und Drang” attitude.

Overall, about 425,000 Sturmgewehr rifles were made for the Wehrmacht before the war ended, and it made a sufficient impression on the allied forces (excuse the pun) to warrant very close examination.

American developments..

At the same time (1939-40) the American Army issued a request for the development of a ‘lightweight rifle’, a handy .30 caliber (7.62mm) automatic carbine, with the intention of using it as a more effective replacement for the military pistol. The cartridge developed for this weapon by the Winchester Company, was based on the .32WSL hunting round, and fired a 7 gram bullet at a muzzle velocity of about 600 m/s (muzzle energy 1,300 Joules). It was the .30 Carbine, or .30 M1 Carbine round (7.62x33mm).

Loaded with a round-nosed bullet, it looked more like a stretched pistol round than a downscaled rifle round, but it was about twice as powerful as most contemporary military pistol rounds. Shortly after the start of trials the US Army dropped the ‘full auto’ requirement. The actual M1 carbine, adopted in 1941, was a semi-automatic only weapon.

Despite its original concept being of a “Personal Defense Weapon” (exactly the opposite to an “Assault rifle”), the M1 carbine quickly became popular among fighting troops for its handiness, maneuverability and rapidity of fire, although limited in range.

By 1944, it became apparent that a fully-automatic version of the M1 would make sense for front-line troops, and the selective-fire M2 carbine was approved for service and put into production towards the end of the war. By modern ballistic standards, it may fall short of being a “true assault rifle”, but nonetheless, it was an important historical weapon which deserves an honorable mention at the very least.

Soviet developments..

It must be noted that the evaluation of lessons learned in wartime brought various practical results. The Soviet Union, whose army learned the value of massed automatic fire through the widespread issue of submachine guns, took the intermediate cartridge concept to heart.

After a series of trials, in 1949 the Soviet Army adopted the world’s most successful “reduced power automatic carbine”, the Kalashnikov Avtomat or AK in short, known to the West as the AK-47. In official Russian terminology, “Avtomat” means “automatic”. Historically this term was used to describe all sorts of hand-held individual automatic weapons; from the full-power Fedorov rifle of 1916, to a series of WW2 era submachine guns (i.e. the PPSh-41 submachine gun was also known officially as “Avtomat obraztsa 1941 goda” or “automatic weapon, 1941 pattern”). The term “Assault Rifle” or rather, its Russian equivalent – never really caught on in Russia.

In the West and in Europe..

Some Western countries also attempted to develop a “reduced power” cartridge. Most notable of these was the so called “BBC committee” (Britain – Belgium – Canada), which promoted a .280 caliber (7x43mm) intermediate cartridge of British design.

However, this concept met with little interest in the USA, where the idea of an accurate long-range (up to 1000 yards / 911 meters) infantry rifle was heavily ingrained into the mindset of the top-ranking officers who made procurement decisions. As a result, the US Army adopted a slightly shorter and lighter .30 caliber cartridge, which nonetheless possessed the same ballistic properties (bullet weight, muzzle velocity, energy and, most important, recoil impulse) as the old .30-06 M2 round. Known as the 7.62x51mm NATO, this round was then forced upon all other NATO members, effectively killing development of “reduced power” ammunition and weapons in the West for some time.

Here we must stop again and re-evaluate the term “Assault Rifle”. It was officially used to name several weapons in various countries after WW2. First of these post-war “Sturmgewehr” rifles were Swiss Stgw.57’s (also known as SIG 510, caliber 7.5×55) and Austrian Stg.58 (License-built Belgian FN FAL, caliber 7.62×51). Both were selective-fire rifles, firing full-power ammunition. Probably the most ironic fact about these “Assault Rifles” is that both Austria and Switzerland are neutral countries and their weapons serve primarily in the defensive role. In most English-speaking countries new weapons were (and still are) designated simply as “Rifle” (i.e. “Rifle, 7.62mm L1A1”, or “Rifle, 7.62mm M14”), without mentioning any specific role, be that assault, defense or anything else.

Now we see that the second generation of “Assault Rifles”, spawned by Stg.44, was in fact split into two groups – one firing “intermediate” ammunition, such as the German Stg.44, Soviet AK-47 or Czechoslovak SA Vz.58, and another, firing full-power ammunition, such as the American M14 and Ar10, Belgian FN FAL, German G3 or Swiss Stg.57.

Therefore we must admit that “Assault Weapon” is an artificial moniker which offers little value compared to the more generic ‘Automatic Rifle’ and ‘Automatic Carbine’ terms. In some cases it is used to specifically separate ‘intermediate power’ automatic rifles from their “full power” cousins (which also have their own class name ‘Battle Rifles’, equally pointless), but its actual historical use proves that it’s not the case.

Keep it real..

Possibly the most accurate designation for a “reduced” or “intermediate” power automatic rifle from a technical standpoint is the original German term ‘Maschinenkarabiner’ or its English equivalents “Machine Carbine” or “Automatic Carbine”, because “Carbine” in general means “short and light rifle”.

The Russian term “Avtomat” in its modern sense is appropriately and officially defined as an “Automatic Carbine” as well. Despite that, the term ‘Assault Rifle’ however misleading it is, has certain gravitas, is in widespread use and let’s face it – just sounds cool – so most probably, it will still be widely used to describe automatic carbines and rifles despite all the facts, as pointed out above.

The same applies to the ‘Battle Rifle’ term, which is often used to describe modern “full power” automatic rifles such as the M14, AR10, HK G3 or FN SCAR-H. In fact, there’s no significant tactical or ballistic difference between the old 7,62x54R AVS-36, AVT-40 or FG-42 automatic rifles of the WW2 era and most modern 7.62×51 automatic “battle” rifles.

Now let’s get back to the history of automatic rifles. As we noted before, by the early 50’s, the East (USSR and its satellite states) had begun to arm their infantry with intermediate-cartridge weapons (automatic and semi-automatic carbines, as well as light machine guns). Full-power rifle cartridges were kept mostly for platoon-level medium machine guns, as well as for sniper rifles.

The West (NATO and many other countries) went the “full-power” road with the adoption of the 7.62×51 NATO round, as developed in the USA. Despite all of the stubborn efforts the US Army went to, to prove that its choice of new round was the right one, practical experiences of the time proved that this was not the case.

Fully automatic fire from the newly designed 7.62mm NATO rifles was ineffective to say the least, and many countries either adopted the new rifles as semi-automatic from the start (as the UK did with their L1A1 SLR), or later converted most of their selective fire rifles to semi-auto only (as the US Army did with their own M14 rifles).

In semi-automatic fire mode, the long range potential of the 7.62mm NATO round was basically lost due to the limitations of using iron sights and the Mk.1 eyeballs of your typical infantryman. Concurrently with these changes, a lot of research was done to find ways to improve the effectiveness of infantry fire. Not surprisingly, this research pointed out what was already known by 1918 – the capabilities of the average soldier in a typical combat situation limit effective rifle fire to 300-400 meters maximum. This “old” finding, along with the new concept of “salvo” firing (to achieve a hit-spreading “shotgun effect”, which could compensate for slight aiming errors) resulted in the decision to decrease the caliber of infantry weapons from the typical 7-8mm down to about 5-6mm or less.

This decrease offers several advantages compared to “standard caliber reduced power” ammunition, including faster bullets with flatter short-to medium-range trajectories, decreased weight of ammunition and guns, and reduced recoil.

Several ambitious but largely unsuccessful research and development programs ensued. These centered on subcaliber flechette rounds, multi-bullet rounds, micro-caliber bullets (4mm and below) and caseless ammunition. These were conducted in the USA, Germany and elsewhere, but practical results were achieved only with conventional ammunition of .22” caliber (5.56mm). These developments happened in the USA during the late 1950’s in conjunction with the development of the Armalite AR-15 / Colt M16 rifle.

This brought to life what could be described as a “third generation of assault rifles”, however artificial this distinction may be in reality. Technically, these ‘third generation’ weapons were selective-fired automatic rifles or carbines. They fired reduced power, reduced caliber ammunition. Inspired by developments in the USA, by the late 1970’s – early 80’s, this concept caught on both in the West (with the adoption of an improved version of the American 5.56mm cartridge as the next NATO standard rifle ammunition in 1979); and in the East (with the Soviet Army adopting its own version of the small-bore reduced power cartridge in the form of the 5.45×39 round in 1974 concurrently with the AK-74 rifle).

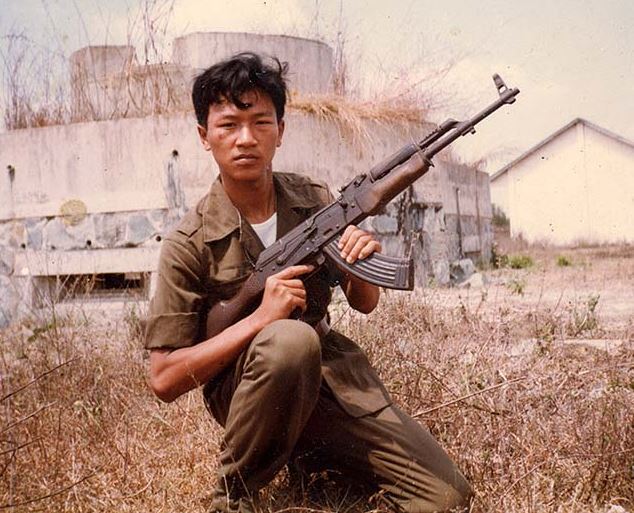

The Vietnam war was the first major conflict where both sides used intermediate power automatic rifles (“Assault Rifles”), such as the Soviet Kalashnikov AK and AKM (above) and American M16 (right) |

|

Today, almost 50 years later, most armies of the world still use this “third generation” rifle ammunition (reduced power, reduced caliber) for standard infantry rifles and squad support weapons. Essentially, the weapons designed in 2014 are not much different from those designed in 1964 or so, except for the use of more modern materials and finishes. That’s because they all fire the same ammunition.

The limited success of the so-called bullpup configuration rifles (for instance the Steyr Aug) also does not add much to the overall combat capability of the rifle-armed soldier. Not to mention the fact that bullpup automatic rifles were designed and tested during the development and evolution of the 1st and 2nd generations of individual automatic rifles.

A more powerful trend..

Another modern trend is an attempt to bridge the gap between full-power, standard caliber and reduced-power, reduced caliber ammunition with the introduction of a few “more powerful than intermediate” rounds such as 6.5 Grendel or 6.8 Remington SPC. These rounds are surprisingly close in basic ballistic properties to the century-plus old warhorses such as 6.5x50SR Arisaka, except that modern rounds have shorter and lighter cases (thanks to improvements in propellant chemistry) and bullets with an improved shape.

Therefore, in terms of overall performance, any modern 6.5mm – 6.8mm “Assault Rifle” is not that far removed from the 1916-vintage Fedorov Avtomat, which fired 6.5mm Arisaka ammunition. The most notable differences between modern and century-old guns would be materials, manufacturing techniques and overall reliability, especially in harsh and adverse environmental conditions.

The key factor that allows modern soldiers to be noticeably more effective in terms of hit probability is in fact, not the rifle or kind of ammunition but sighting equipment. New telescopic day- and night sights greatly enhance shooter performance at medium and long distances, and red-dot sights bring short-range performance under dynamic conditions to a whole new level, compared to the old-style iron sights.

However, in most cases those sights are not unique to any given weapon, and, in theory, anyone with access to a near-century-old weapon such as BAR 1918 or Fedorov 1916 could outfit it with modern sights with some minor gunsmithing.

The circle is complete..

One interesting recent trend is a slow but noticeable comeback of the full-power automatic rifles firing 7.62×51 NATO ammunition. For some time these rifles were issued mostly in semi-automatic, designated marksmen versions, with the intention of increasing the reach of small infantry units armed with 5.56mm weapons in desert or mountainous terrains such as Iraq and Afghanistan.

However, it appears that one such rifle per squad is often not sufficient to fight enemies who are using distance, natural cover and modern body armor for protection against small arms fire. Therefore, several companies worldwide now offer 7.62mm automatic rifles which are intended for individual, rather than squad-support use. To name a few, there’s the FN SCAR-H from Belgium, HK 417 from Germany, SIG 716 and 751 SAPR from the international SIGARMS Company.

Most of these weapons are intended for Special Forces, but in May 2014, the Turkish Army, which (by the way) is the largest NATO military force in Europe, announced its adoption of the MKEK MPT-76 rifle, which appears to be a general issue, select-fire weapon based on the German HK 417.

The Turkish army has plenty of actual combat experience with three of the most widespread infantry rifle cartridges of today – 5.56×45 NATO (in license-built HK 33 rifles), 7.62×39 (in imported Kalashnikov AKM rifles) and 7.62×51 NATO (in license-built HK G3 rifles). And it seems that Turkish infantry can put up with a decreased ammunition capacity in hopes of getting a more effective and far-reaching weapon. With these weapons, automatic fire is reserved for rare, but still probable (at some point) situations such as ambushes or CQB, and most shooting is to be made in deliberate, aimed semi-automatic fire.

A US Navy SEAL demonstrates his FN SCAR-H Mk.17 Automatic Rifle, chambered for full-power 7.62×51 NATO ammunition

Back to square one?

In a sense – yes, because, as we’ve seen above, in terms of ballistics most modern weapons are very close to first-generation weapons dating back to WW1. However, the rapid evolution of sighting equipment, with low-power telescope sights and red dot (collimating) sights (and especially with the emerging class of electronic sights with built-in ballistic computers and other digital sighting aids), helps to stretch the envelope of effective small arms fire beyond the previous capabilities of intermediate-power ammunition.

Final note

There’s another misleading term in circulation in the USA, the infamous “Assault Weapon”. This has no technical or tactical relevance whatsoever. It is simply used as a label to mark whatever weapon is not liked by certain US politicians in an attempt to make this weapon look “evil”. Put simply – an effort to ban it from civilian sales and ownership.

In a tactical sense, almost any weapon, from a stone or wooden club through to a flintlock pistol or modern semi- or even fully-automatic rifle can be used as a weapon of assault, as well as “weapon of defense”, “weapon of sport shooting or hunting” etc.